The French have cognac. Italians have grappa. The English have their gins, Mexicans have tequila, and the United States their bourbon.

But what about Norway?

Our national spirit is of course… aquavit!

This “water of life” is not only limited to Norway but also Sweden and Denmark, with a few examples also in Germany, Finland, Iceland, the Faraoe Islands, United States and Canada.

When I went home to Norway in May and stopped in at one of the largest “Vinmonopol” (the national wine monopoly where you have to go to purchase wine and liquor) in the country, I was simply amazed at all the variety of aquavits available today.

There are over 90 different varieties in Norway today (probably more as of the time this blog is published).

What exactly is aquavit?

It’s a Scandinavian flavored spirit distilled from mashed grains such as wheat, or potatoes, and generally has an alcohol content of between 42-47%.

The term “Norwegian aquavit” has been protected since March 1, 2011. In order to fulfill this name, the spirit has to be distilled in Norway from potatoes (minimum 95% Norwegian potatoes) and aged in oak barrels for a minimum of 6 months smaller than 1,000 liters, and a minimum of 12 months for barrels bigger than 1,000 liters.

The spirit can vary in flavor, according to which herbs and spices are utilized, and the color too, depending on what barrels are being used to age the aquavit.

In the 15th century, aquavit was distilled from imported wine, which made it expensive, however from the 18th century onwards, this was swapped out with potatoes.

If you’ve been following my blog for any time, you know I’m particularly interested in the history of Norwegian food and culture, why we eat and drink the way today. Providing recipes and tips is simply not satisfying enough to me, which is why I started this blog in an effort to dig deeper into our roots and traditions.

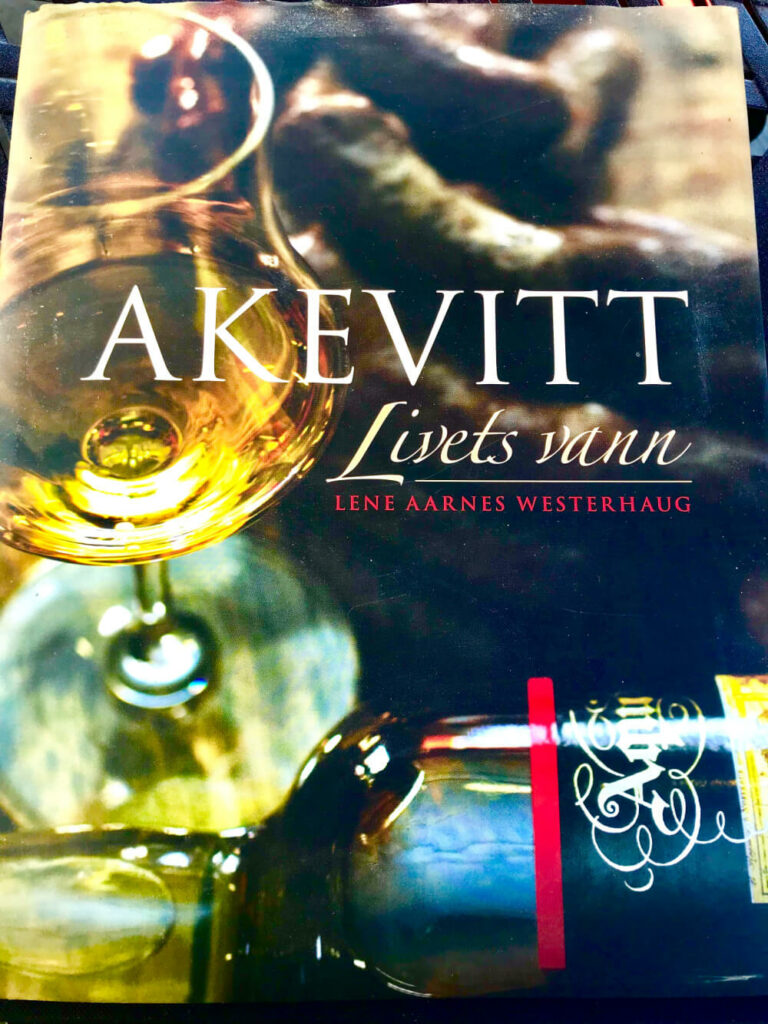

Before I start, I want to say that much of this information is sourced from the Norwegian book “Akevitt: Livets Vann” by Lene Aarnes Westerhaug, which was gifted to me a few years back for Christmas by my sister.

If you can read Norwegian, I highly recommend picking this book up, as it’s one of the most thorough and interesting books on the subject I’ve found.

Let’s dive in from the very beginning:

How did the tradition of drinking alcoholic beverages start in the Nordic culture?

Nobody knows for sure, although people might have brewed alcoholic beverages ever since the first grain was planted following the last Ice Age.

Norse mythology clearly referred to intoxication from alcohol, and the Norse were said to have received their poetic ability and wisdom from drinking Suttung’s mead, a gift from Odin himself.

The Vikings also drank wine, according to the Edda poems, which were documented in the 13th century, after being delivered orally for about 400 years.

We also know that Leif Erikson made wine from grapes that grew in Vinland, today’s Newfoundland. These grapes were not in the same family as the European vitis vinifera grapes we have today and probably tasted a lot different from most wine today.

The Norwegian Vikings didn’t actually make wine, but they sure knew how to get drunk!

When beer became part of European daily life, most of the traditional brewers were women. In Northern Europe, a woman hoping to get married had to be able to brew great beer.

The art of distilling, however, was most likely mastered first by the Chinese, somewhere between 800-100 BC, where they discovered how to distill rice wine.

The Norwegian Viking, although both thirsty and wild, did not know about stronger liquor. Later, central to liquor’s re-discovery was alchemist and professor Arnaud de Villeneuve in Montpellier, France, as well as Thaddeus Alderotte from Florence, Italy. I won’t go into more detail here but refer back to the book mentioned above.

In the 15th century, it became the norm to distill liquor from grains, which had a great influence on the availability of alcohol in countries that didn’t produce wine. In the 16th century, hard liquor also started gaining ground in the Nordic countries.

Hard liquor was produced and used as medicine as early as the 12th century, especially among monks in convents, that functioned as hospitals back then. With all the pests and epidemics running rampant back then, spirits were particularly effective as a healing agent.

When Sweden was hit by the pest at the end of the 16th century, King Johan the 3rd ordered the apothecary Simon Berchelt to create a medicine for the people.

He made two recipes: The people’s medicine “Aquae vitae contra oppotium”, which was flavored with water, ivory, red choral, and a variety of other ingredients. Since the aquavit made patients sweat, it was regarded as an effective medicine.

The other recipe was for a preventative medicine that was called “aquae vitae for poisons and all kinds of illness”.

Princess Anna of Sachsen was one of Europe’s leading aquavit producers. She was born princess of Denmark in 1532 and King Frederik II’s sister. She later married count August of Sachsen.

She was beyond interested in herbs, tinctures, and spirits. She created and shipped her legendary elixirs to kings and emperors all over Europe, and was undoubtedly a central figure in that time’s medicinal world.

Unfortunately, she kept her recipes very secret and when she died in 1585, her 181 aquavit recipes died with her.

Fast forward to Norway, hard liquor was sold in the nation’s pharmacies, even when liquor was illegal from 1916-1926 (primarily because of the war, but later because of a popular vote in 1919).

Spirits like aquavit, cognac, and whisky were supposed to help with anything from melancholy and asthma to pregnancy ailments and diabetes, not to mention the Spanish flu following World War I.

Every Norwegian were allowed to receive half a liter (16 ounces) per consultation but had to wait three days until he or she could receive another dose.

Farm animals, however, would need over two gallons (10 liters) at a time, and there were no limits on how often horses could receive additional doses. Therefore, writing prescriptions for hard liquor was lucrative for the country’s doctors and veterinarians.

The record was said to have been held for a doctor who supposedly wrote 48,000 prescriptions for liquor in a year!

Today no scientific proof exists that proves alcohol has positive effects on health. However, several studies have shown that when consumed moderately, alcohol, when in combination with a healthy diet and active lifestyle, can protect against certain illnesses, such as heart and coronary diseases in older people and heart attacks and Alzheimer’s.

The reason why most people enjoy alcohol, whether, wine or spirits today, however—is that it simply is enjoyable with food and at meals.

Still, herbs in combination with pure alcohol, are still utilized in many ways as medicine, and in Norway, aquavit is regarded as a “digestive”, i.e. it helps digest a heavy meal and is why we often enjoy aquavits with the traditional heavy and fat ladened Christmas dinner.

According to history books, the beginning of Norway’s spirit history began in Bergen. Some insist liquor arrived to the city as early as the 14th century, then as preventative medicine against the Black Death, but it has not been documented.

What has been documented, is that the first aquavit was indeed made in Bergen, according to a letter that was written by officer Eske Bille on April 14th, 1531, sent to archbishop Olav Engelbrektsen in Nidaros in Trondheim. This way, aquavit was also introduced to this second city in Norway.

From the 16th to the 18th century, consumption of hard liquor in Scandinavia was widespread, as it was for the rest of Europe.

Although of varying quality, Norwegian hard alcohol had a great reputation and was considered better than the Danish.

Christopher Blix Hammer is often referred to as the father of Norwegian aquavit. He was an official living in Hadeland, born on the 20th of August, 1720.

He studied mathematics, theology, and law and took over his grandmother’s farm in Hadeland. He wanted to spread the knowledge he gained to the average Norwegian, everything ranging from map drawing, botany, and gastronomy.

He was very interested in Norwegian food based on local produce, herbs, and plants. He detailed the distillation process, and also advocated against overconsumption of alcohol, promoting moderation.

Personally, he abstained from alcohol, but he was of the opinion that drinking liquor was necessary during the winter and that it was even appropriate for breakfast; especially for someone waking up at 2 am, headed to the woods, or working in the barn.

A hilarious quote from a person in the book reads: “It is too early for beer, I’d rather have a glass of aquavit”.

Hammer’s aquavits were based on grain; he didn’t live long enough to experience the potato’s influence on Norwegian spirits. However, he did speak about the potato’s properties and was of the opinion that everything with a sweet taste like potatoes, carrots, and apples could be fermented.

If you’d like to read more about potatoes and the role it has played in Norway and Norwegian history, visit my prior blog post by clicking here.

In Norway today, aquavit is still being produced from potatoes, while in our neighboring countries it’s more common to use grains.

Even though in the 18th century, an acre of potatoes produced a lot more alcohol than grains, there are economic reasons why grain spirits are being used in Sweden and Denmark today. Availability of potatoes is a lot less there than in Norway as well.

One of the most popular Norwegian aquavit with the longest history is Linie, read more about that in the blog archives where I wrote about aquavit here.

An important reason why aquavit is so unique is the addition of spices.

Spices signify culture. Historically, spices were used to cover up the terrible quality of the distilled beverage produced, partly due to a lack of how-to knowledge and the absence of conservation and cooling techniques. Spices were necessary to make it drinkable.

Various spices in aquavit making have been used throughout the years, and have been a mixture of exotic and local varieties.

The selection and combination of these spices play a central role in today’s aquavit. The correct part of the herbs and spices has to be selected, and perhaps even picked at a certain time or dried in a certain way. Not to mention, the herbs and spices must be conserved and stored under ideal conditions.

Per the legal definition, today’s aquavit is a farm spirits based on caraway and dill, but there can be a number of other spices included.

Other spices and herbs used are juniper berries, fennel, iris root, chamomile, coriander, star anise, angelica root, wormwood, celery, lemon, bitter orange, curaçao, and jasmine to name a few. Gone are the days when lead from church windows, snake blood, and elk hooves were used—thank goodness for that!

In today’s production, spices are macerated in a neutral spirit to draw out the flavors and aromas, not unlike how you achieve flavor by dunking a teabag in water. The resulting alcohol percentage of the aquavit depends on what type of spices are used.

Dried herbs generally require a lower alcohol percentage than fresh herbs.

There are also different maceration methods like percolation and vapor infusion, cold compounding, and others.

The purpose of this article isn’t necessarily to go into detail about production methods, as different producers apply different techniques, but clearly, the skillset and knowledge today have been vastly improved even since the 1980s and have resulted in a world-class spirit.

Since the beginning of production, aquavit is aged in oak barrels. In Norway, barrel aging of aquavit made from potatoes has a long history.

Typically, 500-liter oloroso barrels from sherry production are used. In later years, barrels from the port and madeira industry have been employed as well, but only after the aquavit rests in sherry barrels for some time.

There are un-aged aquavits on the market in Norway (Arcus being one company that produces a version).

In Denmark and Sweden, aquavits are rarely barrel-aged, although more of these have popped up in the later years. In 1988, the first Christmas release of aquavit, “Juleakevitt” took place.

Though not super popular at first, juleakevitt has become a yearly tradition to this day for almost every aquavit producer.

Unaged aquavit: (Clear)

Today there are even “summer” aquavits like this!

Aquavit is best enjoyed at room temperature, in order to properly be able to smell and taste all the aromas and flavors from the spices and herbs.

I know of many Norwegians who put the aquavit in the freezer and like it super cold, but it is better to add an ice cube or a dash of water to it.

The exception is perhaps some of the un-oaked or un-aged aquavits, where serving it chilled will dampen the sensation of high alcohol. You will see many Swedes and Danes putting their aquavits in the freezer, but their aquavits are, as I mentioned prior, not aged and they also have a different snaps culture than we have in Norway.

Another important part of enjoying aquavit correctly is the type of glass it is served in.

Cognac glasses are not the way to enjoy barrel-aged aquavit, however, tulip-shaped glasses made for whisky, cognac, and Armagnac might work.

Distiller Halvor Heuch who works for Arcus developed a special aquavit glass in collaboration with Austrian glassmaker Riedel. The purpose was to produce a glass that would capture the aromas of oak, sherry, and spices all in one.

Through a tasting panel, they decided on the perfect glass after trying 12 different ones. Riedel’s aquavit glass comes in two versions; glass-blown in the exclusive series Sommelier, and machine produced in the slightly rougher series Vinum.

So when do you drink aquavit?

Any time of course!

Although Christmas is typically associated with this drink, it has become more common to enjoy it year-round. During Christmas, beer and “dram” is almost as important as our traditional dinners. The fatty, meat-dominated dinners are seen as a perfect companion to aquavit (as is lutefisk), which helps “cut” through the grease and aids digestion.

Now that I don’t eat meat or fish anymore, I have been experimenting with plant-based dishes.

Vegetarian versions of stews like brennsnut and lapskaus lend themselves well to aquavit, as does more exotic dishes like Moroccan tagines and Indian curries when paired with sweeter aquavits. Try it with creamy soups like parsnip or sunchoke (the earthiness of the vegetable goes beautifully with the oak influence in the spirit).

Aquavit is also fabulous in combination with cheese. Of course, I’m talking about plant-based cheeses made from nuts here, which will harmonize well with a fruity style. I love Miyoko’s Kitchen cheeses, her cashew based Fresh Loire Valley or Alpine “goat cheese” will pair nicely with a milder and lighter style aquavit, while her smoked farmhouse cheese wheel is super tasty with a darker, heavier style.

It’s important to pay attention to the sweetness, spices, alcohol strength and richness of the aquavit, and pair these accordingly with sweet, sour, salt and fat in different dishes.

It’s important to note that just because you’ve tasted one kind of aquavit, and perhaps wasn’t fond of it, don’t despair. This doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t like aquavit!

There are so many different versions now; mild and strong, lighter and fuller, and of course; a spectrum of flavor variations.

Unfortunately, Norwegian aquavits are not readily available on the U.S. market as of today, but my dream is to change that.

In the mean time, you’ll just have to book a trip to Norway—ideally, Up Norway’s new Vegan Trail tour which was recently created and I’m super excited about.

This way, not only will you get a chance to sample the authentic, small-production aquavits, but also travel along the famous cider route of Hardanger, as well as experience the city of Bergen, where aquavit got its start.

See you in Norway—skål!

I’m going to print this for my dad. At 85 he loves his Aquavit and is proudly all Norwegian. He lives in Minnesota but is able to find a steady supply of lutefisk around the holidays. Thanks for the info!

Wonderful, Audrey! Your dad sounds awesome! Tell him skål from me! 🙂

Well, you can purchase Lysholm Linie Norwegia Aquavit in Oregon and Washington State……

I noticed that you are consistently using the word “corn” as an ingredient. This should be “grain”, called “korn” in Norwegian. Corn is called “mais”, and was not part of the Norwegian farming until the l950s, at least in Hedmark. The one farmer I knew who grew it then, used it for pigs’ feed. Today people eat corn as well. The main Norwegian grains were oat, wheat, rye and barley, so it would be one of these that were used for alcoholic drinks.

Thanks for the correction Randi – my English still needs improvement even after 20+ years here… I’ve gone ahead and corrected this. I hope you enjoyed some aspects of the article still!

Was akvavit served in pointed glasses, which forced you to drink it immediately, because you couldn’t put it down without spilling it ?

That’s an interesting theory but not, the glass shape has more to do with bringing out the right aromas and flavors (glasses should always have a stem) plus there’s an aesthetic element to it too – an aquavit glass should look stylish on your dinner table 🙂